While in the early medieval times love mainly meant a love for God, in the 11th century the ideal of love between a man and a woman emerged in courtly literature. At the centre of it there was beauty and the irresistible charms of a woman, which turned the knights into humble servants of their ladyloves (generally the wives of their lords). This is how courtly culture turned upside-down the medieval mindset whereby the man was the conqueror and the woman his servant.

At the same time another theme became popular, first in literature and later in art, which, depending on the author, the setting and the audience, either warned men against the charms of women, or mocked those who had become the slaves of love. The popular examples included the strongest, bravest, and smartest men of the Old Testament, ancient history, and courtly literature; the so-called exempla virtutis (examples of men of virtue), who got into trouble through their passion for women. The idea originated from Christian sermons, the aim of which was to show the fatal consequences of earthly love and to guide back to God those who lost their way in the embrace of a woman. Art and images helped to spread this message and intensify its effect at a time when literacy was a privilege of the clergy and the representatives of the upper class, which were few in number.

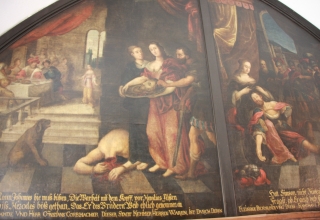

In the beginning, these characters were depicted separately in art, but in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the two couples started being depicted together – Samson and Delilah (Samson, the strongest man in the Old Testament, lost his power and life by revealing the secret of his strength to the woman who had seduced him) and Aristotle and Phyllis (Aristotle, the smartest man in the ancient world who lost his senses and dignity at an old age through the charms of a woman). So that it would be easier for their 14th century contemporaries to identify with the characters, an addition was made to the stories of the Old Testament and ancient history, with the introduction of the brave knights of King Arthur, notably the knight Tristan, who broke an oath of fealty to his lord King Mark by falling in love with his wife Isolde.

All characters mentioned above are also depicted on the benches in the Town Hall of Tallinn. They are accompanied by other important characters from the Old Testament, such as King David, who indeed freed his people from the Philistines (it is symbolized by David´s fight against Goliath), but lost his dignity and honour as a king because he was not able to resist the charms of Bathsheba, the wife of the commander of his troops.

In the Old Testament, in addition to Samson and David, the forefather of mankind, Adam, who sinned because of Eve, and King Solomon, who started worshipping the pagan gods of his hundreds of wives and turned his back on the true God, are also represented as slaves of love. From ancient history, another favourite character besides Aristotle is the great Roman poet Vergil. As for the characters from the age of chivalry, alongside Tristan, other knights of King Arthur´s Round Table are mentioned, the most popular of whom are Ywain and Lancelot.

The stories about all of the men mentioned above imply that if the strongest of heroes cannot resist the lusts of the flesh, they become slaves not only of their passion, but also of women. This topic was defined in the German cultural space with the term Weibermacht (power of women) or Weiberlist (cunning of women), referring to the idea that women use their charms consciously to manipulate men.

The initial idea of the slaves of love, which emerged in ecclesiastical circles throughout the Christian era, was mainly moralizing. Further interpretation of the images depended on their location, patron or person who commissioned them, and of course the audience.

The slaves of love are depicted in abundance in churches, on choir stalls and their misericords or small wooden shelves on the underside of folding seats (Cologne Cathedral in Germany, Exeter and Chester Cathedrals in Great Britain, etc.). On those mercy seats, on which the monks could lean during long services, the ungodly characters and scenes are depicted with humour, as if to contrast the celibacy of the monks.

The thematic images were depicted on the facades of buildings, column capitals and wall hangings (Tristan and Isolde on the façade console of the Town Hall in Bruges, Samson and Delilah on the door frame of a house in the medieval town of Cluny, Aristotle and Phyllis on the column in Lyon Cathedral etc.). Among the latter, the most well-known is the so-called Malterer tapestry in the Dominican nunnery in Freiburg, and the tapestry in the Town Hall in Regensburg (both are in Germany). The images on the hanging in the Town Hall warned the men who ruled the city against the charms of women and the blinding power of love, which deprives men of their wisdom, bravery, and physical strength – all of the qualities which turn them into great leaders and conquerors. As for the hangings in the nunnery, they probably symbolized the fear of the women hiding in the nunnery, who had chosen the love of God instead of earthly love, worldly life and sinful love. Besides, women often used nunneries as a shelter where they could escape painful and dangerous births, which in medieval times frequently ended in the death of either the child or the mother. It was believed that God was punishing women for Eve´s sin, the Fall of Adam in the Garden of Eden, with the pain they had to endure while giving birth. The nunnery provided women with the chance to live a virtuous life, like the Virgin Mary, and to find redemption through commitment to God.

One can come across the stories depicting the power and cunning of the charms of women on the ivory jewellery boxes and mirror cases belonging to noble women, and also on wooden combs and caskets. Instead of providing a warning, those luxurious beauty objects were rather hiding romantic dreams within themselves and helping their owners realize the irresistible power of female beauty and primeval desires.

The circulation of the images depicting the slaves of love was facilitated by the introduction of typographic art in the 15th century. The series of woodcuts named Weibermacht (the power of women) by Lucas van Leyden, a Dutch artist, completed in 1512, was so successful among art collectors that the artist made another series, the so-called small Weibermacht. In 1521, another Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer, designed wallpaintings for the Gothic Hall in the Nuremberg Town Hall with characters of the same theme – Samson and Delilah, David and Bathsheba and Aristotle ridden by Phyllis. Unfortunately, his design was not brought to life, but his drawing survived and can be seen in the Morgan Library and Museum in New York.